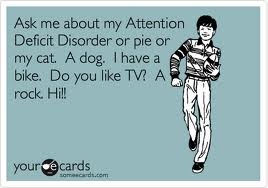

I could never shut up as a kid in school. I talked incessantly, being told to be quiet, several times a day, only to start talking again moments after being reprimanded. I was smart, but social, my teachers would say. And I don’t think I ever got a report card that did not state in loopy penmanship, “talks too much,” and “does not work up to her potential.” In kindergarten I had to sit in the corner by myself one day because I was talking. I came home sobbing, and told my older sister about my misery, who replied, “Welcome to the Friedman motormouths.” As young as I was, I somehow knew that I was following in a less than desirable family tradition. When I had my son, it didn’t take long for the letters A.D.D. to be bantered around. (SQUIRREL!) He was a tornado of activity from his earliest moments. And while he was clearly super bright and engaging, his activity level and curiosity dogged us from his earliest school experiences. I won’t go into the whole, VERY, VERY, VERY, VERY LONG story in detail, but after having him tested in 2nd grade, we found he did indeed have A.D.D., and the school thought he should be put on medication, but we resisted, feeling adamantly opposed to the idea of medicating a 7 year old. By third grade, with the help of an exceptional therapist, who was acting as a sort of parent coach to us, supporting us to make the right decisions with Jake, and a highly experienced, and extraordinary 3rd grade teacher, it became obvious that it was time to seriously consider medication. My husband took a month off from work, and the two of us immersed ourselves in making this decision. We read everything we could, and even visited the renowned Edward Hallowell, the author of “Driven to Distraction.” It wasn’t easy, but drowning in research and exhausted from thinking, we decided to try it. And within three weeks, his teacher called him an “ideal student.” Jake was feeling good about himself, because, what his medication did for him is the same thing as glasses do for a person with nearsightedness. As my husband and I learned about A.D.D., we realized that we both had it, but had learned strategies to cope with it. There was no such moniker as A.D.D. when we were kids, so therefore there was no help for it (the truth is there was no drug for it, so there was no name for it). My daughter, a chatter box like her mom, wasn’t diagnosed until fifth grade, but of course, when the symptoms appeared, we knew exactly who to see, and how to test. But don’t cry for us, Argentina! Yes, we are the A.D.D. family, but I’ve got to tell you, I’ve found that A.D.D. people are some of the most creative and interesting I have met. Those three letters may make it more difficult to focus, but they also seem to make it more possible to take in lots of information, and tap into creativity in fascinating and off-beat ways. And more than not, A.D.D. people are often quite social and have an insatiable curiosity for life. We think of it as a positive in our family. And we treat it like that. I’m not saying, it doesn’t require more work to live with A.D.D, but I am saying I’m grateful for it. Yup, I actually am. It’s kind of a cool sort of malady, once you get the hang of it. It’s thought that Einstein, Mozart, da Vinci, Churchill, Walt Disney, Alexander Graham Bell, and John Lennon, among other creative and high-achieving people had it, too. And while I may not contribute anything nearly as monumental, or significant as those examples, I’m pretty darn happy to be in their company.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.